Up & Down

How art in 2013 reflected economic inequalities and suggested alternative ways forward

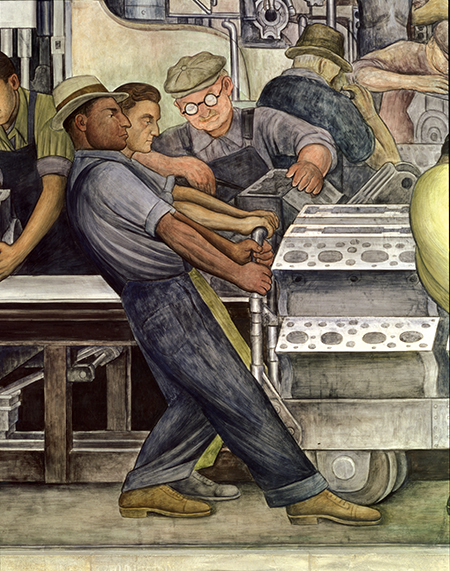

Diego Rivera, detail from Detroit Industry mural, commissioned by the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1933. Courtesy: Bridgeman Art Library and The Detroit Institute of Art, Michigan

From where I sit, which is in New York, the mainstream conversation about art felt particularly disconnected in 2013, full of the angst of going nowhere. There’s a material basis for this disconnection. As is now well accepted, art’s seemingly bulletproof market is driven by its unique connection to the worldwide phenomenon of growing inequality. And, despite a global economy suffering the equivalent of permanent indigestion, the very rich continued to get very-richer in 2013 – prompting the art market to dutifully produce a stream of chipper headlines. This will be remembered as the year that, in November, Christie’s New York broke records with a US$692 million postwar and contemporary art sale – over a half a billion dollars in business on just 67 works of art: a staggering feat. It’s hard, sometimes, to hear anything at all over the sound of the cash register.

As the money poured in, the big galleries got bigger: Hauser & Wirth, Galerie Perrotin and David Zwirner all debuted flashy New York branches; Lehmann Maupin followed White Cube and Gagosian to Hong Kong; Marian Goodman announced plans for a London outlet, joining her New York peers Zwirner and Pace, who arrived in 2012.

Continuing its recent trend, the art got bigger too. This included the usual Big Stars like Jeff Koons, who debuted simultaneous shows of new work at Gagosian and Zwirner in May, turning out a fresh line of larger-than-life baubles and photorealist paintings. But it was the strangely similar impression left by the blockbuster gods’ simultaneous beatification of Paul McCarthy and James Turrell that really illustrated how Bigness has taken hold and has its own logic, independent of local artistic style.

In May, McCarthy was seen high above Randall’s Island, mocking Jeff Koons’s signature motif with a king-sized balloon-dog. Then he went and inflated his own work to new and unprecedented dimensions, filling Hauser & Wirth’s sprawling new Chelsea space with ‘Rebel Dabble Babble’, a clamorous multiscreen epic of sexual humiliation inspired by Nicholas Ray’s movie Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Its scale and scope was then topped by McCarthy’s own concurrent show at the Park Avenue Armory (increasingly the go-to place for fathomlessly huge environmental art works), ‘WS’, a retelling of Walt Disney’s Snow White fable as a debauched house party of masturbating dwarves and anally expulsive princesses, blown up to IMAX size and projected on the walls around an enchanted forest so immersive that it took 85 articulated trucks to bring in all the parts.

Turrell, for his part, owned summer in the us with three simultaneous shows – at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts and New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum – not to mention a pair of splashy projects in Las Vegas (at a mall and a Louis Vuitton store). The New York outing, at least, was a disappointment, transforming the Frank Lloyd Wright building into the walk-in equivalent of a comforting nightlight. I hear Los Angeles did Turrell more justice (though not Vegas).

Red wine and white wine taste more or less the same, if you add enough Kool-Aid, and what strikes me about the comparison of McCarthy with Turrell is that, despite the fact that these men are about as aesthetically different as can be, the effect of super-sizing in both cases transformed their artistic practice into their own opposites. Surely McCarthy’s scabrous art is partly justified by the fact that it is a truly intimate rejection of ‘mainstream’ ideas of normalcy – but this moral becomes increasingly difficult to take seriously as its particular form of depravity becomes increasingly mainstreamed, something the epic scale of his new work hits you in the face with. As for Turrell, at a certain scale, and jostling against the record-breaking New York tourist crowds, his installations simply cease to be about the purity of perception and the spiritual quality of light, and instead join a class of gee-whiz civic spectacles like, say, fireworks displays.

Then there were the celebrities, as the fashion and entertainment industries continued to harvest visual art for cheap cred. Even the apocalyptically countercultural McCarthy featured Hollywood polymath James Franco, as well as adult film star James Deen. For the most part, the various art-celeb crossovers were tiresomely familiar, locked in the same tight circle of money-approved safe references.

Lady Gaga got naked and humped an enormous crystal in an unintentionally hilarious promotional video for Marina Abramović’s performance art institute in Hudson, New York. It was an attempt to display the so-called Abramović Method in action, but was really a demonstration of what surrealism looks like when stripped of the unconscious: weirdness for weirdness’s sake. In her club anthem ‘Applause’ (2013), Gaga went on to sing about her desire to become a Jeff Koons sculpture (‘One second I’m a Koons / Then suddenly the Koons is me’), a reference that shows less her intellectual precociousness and more that she urgently needs to read about art in someplace other than W magazine. Jay Z, in his icky rap-mogul-as-art-collector jam, ‘Picasso Baby’ (2013), at least cast his net a little wider, referencing Jean-Michel Basquiat and George Condo, even Mark Rothko and Francis Bacon. But he still circled inexorably back to Koons (‘Jeff Koons balloons / I just want to blow up’), along with his exploits bidding at Christie’s and having ‘twin Bugattis outside of the Art Basel’.

It just showed how art has entered the popular imagination as a symbol of grotesque, aspirational wealth. Jay Z’s weirdly awful concept video for ‘Picasso Baby’, filmed at Pace Gallery and debuted for all the country to see on hbo in August, featured a rogue’s gallery of New York art types lamely facing off with the rap star. It was embarrassing enough that you’d hope that it would end the crossover phenomenon. But it probably won’t.

Meanwhile, beneath the fizz of big money and celebrity cameos, art was in fact not immune – not at all – to the predations of the Age of Austerity. This took rather different forms on different sides of the Atlantic. In the UK, public art funding has been hit again and again, and the year was about finding ways to do more with less, of institutions banding together, as well as fitful acts of protest: in late May, a walk-out by members of the Public and Commercial Services union briefly affected attractions from the National Portrait Gallery to Stonehenge; in September, arts supporters staged a symbolic ‘human chain’ around the National Gallery in protest of cuts and ‘zero-hours’ contracts, which fail to give museum workers even minimum guarantees of work.

In the US, art funding largely stayed out of the headlines, though this is mostly because the National Endowment for the Arts is by now so anaemic that it is hard to credit it as the face of Big Government. The alarming go-to symbol of the relentless pressure that an increasingly unequal society put on art was the plight of the Detroit Institute of Art. As Motor City declared the largest municipal bankruptcy in us history amid a soaring art market, chatter naturally turned to whether selling off a few dia masterpieces might soften the blow. Christie’s experts were brought in to appraise the collection. The art community rallied; the idea of auctioning Diego Rivera’s famed Detroit Industry murals (1932–3) to appease the moneylenders revolts the conscience.

For my money, the incident also illustrates in the most diagrammatic fashion how political solidarity is not a bonus added on top of arts advocacy, but an urgent task. Saving Detroit’s art is a worthy cause. Yet in a city where the streetlights are being turned out and pensions pillaged, art is eventually bound to be turned into a further symbol of a divided society, if pursued in isolation. The case for political alliance is urgently clear.

Inequality corroded the foundations of art in another way. All year in New York, the inescapable conversation was about real estate: where could you afford to live, let alone work? Sometimes the official conversation channelled this anxiety in oblique, academic-sounding form: Creative Time, the public art group, held its annual summit on ‘Art, Place, and Dislocation in the 21st Century City’, while later in the year moma launched a show on ‘Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities’. Sometimes, the anxiety was not coded at all: musician David Byrne penned a manifesto stating that the city of the One Percent had become uninhabitable for all but the least emerging of artists. But always, at street level, the stakes were brutally clear.

In an earlier era of urban transformation, modernism went from being a quasi-utopian language of efficiency to the symbol of faceless authority, via the corporate skyscraper. Groovy postmodernism, with its glass curves and skewed facades, seems well on its way to a similar symbolic depletion, having become the lingua franca of soulless luxury condos (‘New York by Gehry’, anyone?), the most hateful and hated urban structures of the day. New York, deemed one of the world’s safest markets for investors looking to park some loose capital in a trophy property – ‘the equivalent of bank safe deposit boxes in the sky’, one observer told The New York Times – continued to swamp its residents with a seemingly unending tide of rent rises and unaffordable development. As Bushwick, the current outpost of hopeful young (and mainly white) artsy types, was cannibalized by its own cool, the year saw a few artists begin an attempt to organize communal ownership schemes, panels and speak-outs, and some belated solidarity with the longer-term, more multi-racial residents being forced out. But the hour was late. With New York hitting records for homelessness, the situation seems, in its own way, as dire as the bankrupt 1970s. Only, back then at least scarce resources gave people the freedom to create, whereas now, it is difficult to think of anything other than where people might stampede to next.

At its highest levels, art seemed aware of its disconnect, desperate to escape from itself. Such was the subtext, I think, of curator Massimiliano Gioni’s ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’ show for the 2013 Venice Biennale, which wrapped name-brand art stars in copious quantities of exquisitely obscure figures from the wider regions of aesthetic production, from Carl Jung’s psychoanalytic drawings to the titular proposal for fantastic architecture by Marino Auriti, a virtually unknown Italian-American mechanic and self-taught architect. In the embrace of the once-

marginal ‘outsider’, the art world acknowledged the social vacuum that the ‘inside’ had become.

This hunt for outsider relevance explains a lot of the year’s obsessions. How else to make sense of the sage-like status assumed by the worthy Theaster Gates, who has laboured to channel art-world resources to Chicago’s hard-pressed South Side and was fêted in 2013 by the fashionable set from Basel to São Paulo? Or the uneasy mix of big-hearted community engagement and poverty tourism that informed Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument, an installation-cum-community-centre sited temporarily in a Bronx housing project over the summer?

The through-the-looking-glass twin of the year’s obsession with stars and sales was the increasing institutionalization of ‘Socially Engaged Art’ (sea), a genre that blurs the lines between progressive activism and public art. Everywhere beyond the market centres, and even to a certain extent within them (see Hirschhorn and Gates), pushing the limits of artistic ‘community engagement’ was the hot topic. In February, Suzanne Lacy’s ‘Silver Action’ used London’s Tate Modern as a platform for a dialogue between veteran feminist activists; in October, Lucy and Jorge Orta brought together some 900 people in Philadelphia for a vast communal meal and a conversation about food policy; and so on.

There are pitfalls as well as opportunities in this emerging vogue. In classic dialectical fashion, such big-hearted projects are a rejection of crass economics, but they also bear a closet connection to what they are rejecting: this is art appropriate to the needs of funders and institutions keen to prove that their programming has ‘real-world’ benefit. Somewhere in the background, the rhetoric of ‘social practice’ tacitly assumes that ‘normal’ art is a frivolous luxury. Still, it is hard to argue that the sea debate doesn’t open a conversation worth having.

Creative Time split its 2013 Annenberg Prize for Art and Social Change between the Palestinian artist Khaled Hourani, organizer of the 2011 ‘Picasso in Palestine’ project, and the American pioneer of ‘legislative art’, Laurie Jo Reynolds, who has dedicated her artistic career to assisting a campaign to shutter the hellishly inhumane Tamms ‘Supermax’ prison in southern Illinois. Accepting the award, Reynolds ceded the stage to three of her collaborators – freed inmates Darrell Cannon and Reginald ‘Akkeem’ Berry, Sr., along with Brenda Townsend, mother of a former Tamms inmate – who staged a simple piece of activist performance art, standing together silently onstage in the dark, each of them waiting one interminable minute for each year that they or their loved one had spent in solitary confinement. Like most serious art, this basic gesture found a symbolic way to illuminate an entire other world – in this case, one we’d like to see banished for good.

And yet finally – fitting for a year of disconnection – the most important art story of the year occurred outside the world of art. The political narrative that ruled 2013 was the Edward Snowden leaks. The affair certainly offered copious lessons for artists, not just for what they directly revealed – a world of total electronic surveillance – nor even for what they more indirectly illustrated: how very globally interconnected the contemporary world of discourse has become, when a crusading journalist based in Brazil teams with a British newspaper to unveil the inner doings of the us spy programme, with stops in Hong Kong and Moscow, as if in some kind of homage to the globe-trotting itinerary of James Bond.

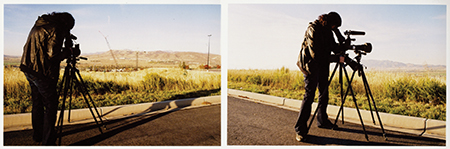

But there is also, as they say in the biz, a real art angle to the Snowden story – a more direct one. Journalist Glenn Greenwald’s partner in routing the Snowden information to the public was the filmmaker and artist Laura Poitras. And it was Poitras’s experience in making a documentary film series (‘9/11 Trilogy’, 2006–ongoing), partly set in Iraq and showcased at the 2012 Whitney Biennial, that led to her own personal journey, probably the most significant intersection of art and politics since Ai Weiwei became an icon of Chinese dissidence three years ago. As Poitras has explained, she found herself placed on a us ‘watch-list’ for her Iraq films, detained dozens of times at the border and was told that, should she decline to share information about her art work, the authorities would simply use their wizardry to harvest her electronics against her will. ‘As a filmmaker and journalist entrusted to protect the people who share information with me, it is becoming increasingly difficult for me to work in the United States,’ she told the New York Times. ‘Although I take every effort to secure my material, I know the nsa has technical abilities that are nearly impossible to defend against if you are targeted.’

Laura Poitras filming at an NSA construction site, October 2011, Utah. Photo courtesy: Conor Proverzano

Here is a story that concerns every artist who makes work that seeks to matter beyond the gallery, about our very capacity to exist as engaged creative subjects. But there is a more hopeful note: as I write this, Poitras and Greenwald are working on the launch of their own news service. Whether they can pull it off is an open question – but perhaps the very idea can inspire some thinking about the alternative institutions, alternative communities, needed to re-connect and re-illuminate our fragmenting world.

By Ben Davis

Source: www.frieze.com