The Royal Academy Show Focuses on “Neglected” British Painter Paul Sandby

LONDON (REUTERS).- Art history has been less than kind to Paul Sandby, an 18th century British painter whose name was eclipsed by contemporaries like Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds. But a new exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy sets out to remind visitors of Sandby’s importance in promoting the status of the watercolor, recognizing the power of print and taking on William Hogarth, whose works he dared to parody.

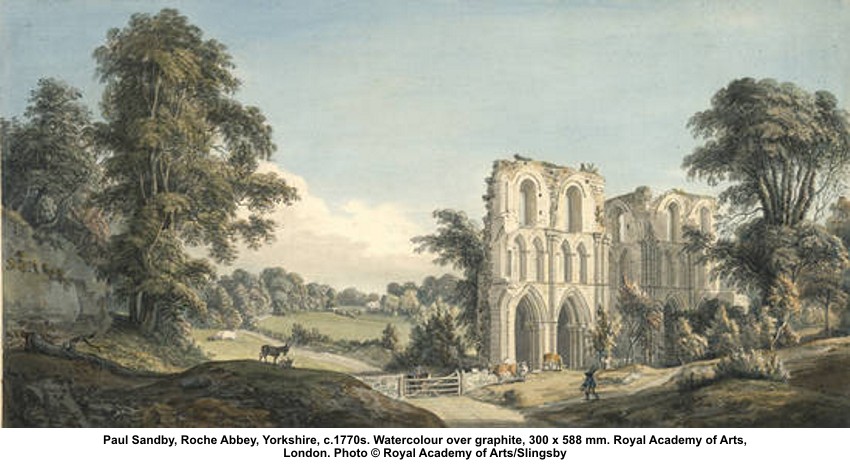

A founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768, Sandby was regarded as “the father of English watercolor,” and in focusing on landscapes and scenes across England, Scotland and Wales rather than Italy, he left an important record of social, economic and political change.

His subjects ranged from street hawkers to battlefields, and sweeping landscapes to grand aristocratic estates, using innovative painting techniques which he passed on to students at the Academy and amateur artists.

Exhibition organizers considered it “remarkable” that such an accomplished painter apparently had no formal training, but learned the basic skills of his trade as a military draughtsman whose early role was to make maps.

As a young man he moved to Soho in London, then the center of the art world, and had the audacity to take on Hogarth, an elder statesmen of British art, in a series of viciously satirical prints. The target of his attack was Hogarth’s 1753 book “The Analysis of Beauty,” which set out with the aim of “fixing fluctuating ideas of taste.”

In one pictorial reply, Sandby depicts a grotesque Hogarth “sinking under the weight of his Saturnine Analysis” and argues, with references that would have been obvious to viewers at the time, that Hogarth copied many of his ideas from elsewhere. Ironically, a series of 12 prints by Sandby depicting the gritty reality of life on the city streets closely echo Hogarth’s own works like the 1741 “The Enraged Musician.”

Sandby sold those prints for three shillings through a London dealer, offering the middle- or upper-class buyer something out of the ordinary to purchase.

In another series of 12 works, his 1776 “XII Views in North Wales,” Sandby uses a technique of etching on to a copper plate with resin and acid to make his prints. “The Iron Forge,” one of the series, shows a stream and mill generating power and churning smoke into the air, and the dramatic effect suggested that for Sandby, industry and agriculture were fitting subjects for an artist.

“This would have been a remarkably modern image for its time, both in terms of technique and subject matter,” the Academy said, adding that its movement and atmosphere recalled the artists of successors like J.M.W. Turner.

Sandby continued to produce pictures of ruins, estates, parklands and streets into old age, but by 1808, the year before his death, he asked the Academy for a pension “owing to advanced age and infirmities and failure of employment.”

Although superseded by a new generation of artists whose works examined the effects of light and movement rather than stressing accuracy in detail, the exhibition underlines how Sandby helped cultivate a market for British landscapes, and, more specifically, for watercolors.

Visit The Royal Academy at : http://www.royalacademy.org.