That Little Lost Boy in Red, Back With His Family

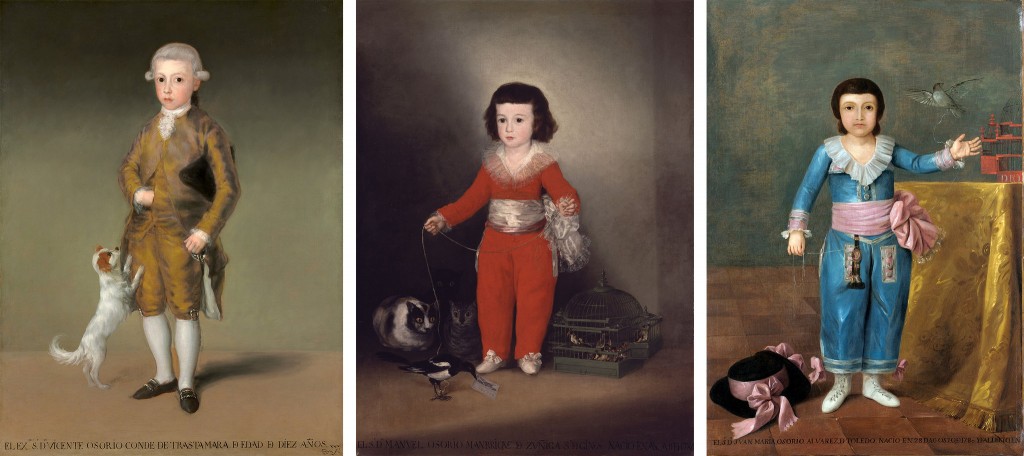

Goya and the Altamira Family The sons of the Count and Countess of Altamira, from left: Vicente, Manuel and Juan, who was painted by a collaborator of Goya’s, in this show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Credit From left, private collection; the Jules Bache Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Cleveland Museum of Art

Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga, the little red-suited boy in the Metropolitan Museum’s prize Goya portrait, died in childhood while his parents were still living. But in the Met’s European Paintings galleries, he has long been an orphan, separated from his mother, whose portrait traditionally hangs in the museum’s Robert Lehman wing, and his father, in Spain.

In “Goya and the Altamira Family,” a small but intensely gratifying exhibition, the Met has reunited Manuel with his parents and three of his six siblings. Organized by the former Met curator (and current chief curator of the Frick Collection) Xavier F. Salomon, it complements the museum’s two Altamira family portraits with loans from the Banco de España, the Cleveland Museum of Art and a private collection.

It’s a rare opportunity to see a single aristocratic family through Goya’s eyes. Surveying the group of five paintings (four are by Goya, and one by his less talented Spanish collaborator Agustín Esteve y Marqués), you notice the ways he brought out resemblances or played with the distinctions of gender and birth order. And you may pick up on more psychological crosscurrents among the portraits, which create an atmosphere of almost awkward intensity. You are, after all, a guest at someone else’s family gathering.

But the show isn’t just about Altamira family dynamics, or even about the extended family of the Spanish nobility. (All of Madrid’s aristocrats were said to be related, and “cousin” was a popular form of address.) It’s about the complicated relationships among portraiture, patronage and legacy, or about the ways a great artist can leave his mark on the family tree.

Goya came to know the Altamiras at a pivotal moment in his career, when he was shoring up his reputation as a pre-eminent court painter. “I have made myself most sought after,” he wrote to a friend in 1786 during a particularly busy period. His projects at that time included a set of tapestry cartoons for Spain’s royal family and a series of portraits of the directors of the Banco Nacional de San Carlos (later the Banco de España).

The Count of Altamira, Vicente Joaquin Osorio Moscoso y Guzmán, was one of the bank’s directors (and an important figure in Madrid society). Goya delivered a classic boardroom portrait, showing the count seated next to his paperwork with a hand tucked inside his red vest, but did not do much to disguise his famously small stature. (The English politician Henry Richard Vassall-Fox wrote that Altamira was “smaller than many dwarfs exhibited for money.”) The table next to him is shoulder-height, and the obtuse angle of his legs and torso suggests that he is seated on an extra cushion.

Nonetheless, the count was happy enough with his portrait that he commissioned Goya to paint other family members. In the imposing painting from the Lehman wing, Altamira’s first wife, María Ignacia Álvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga (a.k.a. Manuel’s mother), balances the infant daughter María Agustina on her lap. She is a feminine and ethereal presence, from her soft nimbus of brown hair down to the delicate floral embroidery at the hem of her blush-colored silk dress. (The pastel palette looks even more faint next to the reds and golds of the count’s portrait.)

Across from the countess’s portrait hangs one of the couple’s eldest son and heir, Vicente Osorio de Moscoso, Count of Trastamara. Although he is just 10 in the painting, he is not very childlike; dressed and posed much like his father, with a three-piece suit and a gray wig, he ignores the playful little dog pawing at his side.

The Countess of Altamira and her infant daughter, María Agustina. Credit Robert Lehman Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

He is an excellent foil for his baby-faced brother, Manuel, who is here — as ever — a scene stealer. Surrounded by his pets, the youngest Altamira boy looks vulnerable and just a little bit mischievous. (The meaning of the animals has been much discussed by art historians, especially with regard to Manuel’s early death, but Mr. Salomon sees the birds and cats as typical props in 18th-century children’s portraiture.)

It’s clear that Goya was heavily invested in this particular work; next to it, the painting of Vicente, with its plain background and more uniform lighting, looks almost unfinished. Even more telling, perhaps, is that he worked his own calling card into Manuel’s portrait. (It’s right up front, in the magpie’s beak.)

Manuel and Vicente had a middle brother, Juan Maria Osorio, who died in infancy; his portrait, by Agustín Esteve, is the interloper in the family reunion. Thought to have been completed after the child’s death, it’s solemn and, compared with the painting of Manuel, heavy-handed in its symbolism. (An open birdcage is inscribed “DIOS,” or “God.”)

In addition to losing two of their children, the Altamiras suffered financial troubles. Like other aristocratic families, they were hit hard by the Napoleonic invasion. The count’s heir (the boy Goya depicted as a serious 10-year-old) was obliged to sell off much of the art collection, but managed to keep the portraits of his mother and siblings; they were scattered only after his death, in the second half of the 19th century. The portrait of his father remained with the Banco de España, which still owns it and normally displays it in a private rotunda alongside the other Goya portraits of bank directors (where it can be seen only by special permit).

Manuel, meanwhile, moved through a series of foster homes (at one point passing through the hands of the legendary art dealer Joseph Duveen) before arriving at the Met as part of a bequest from the collector Jules Bache.

As the youngest son, Manuel, had he lived, could not have been the Altamira heir. But this show makes clear that the Goya portrait has given him a different kind of inheritance, one that has no monetary value and can never be lost or squandered.

By KAREN ROSENBERG

Source: http://www.nytimes.com