Miami Finally Has the Art Museum It Deserves

Hew Locke, For Those in Peril on the Sea, 2011, model boats and mixed media, 79 boats, installed in the lobby, Pérez Art Museum Miami. COLLECTION PÉREZ ART MUSEUM MIAMI, MUSEUM PURCHASE FROM THE HELENA RUBINSTEIN PHILANTHROPIC FUND AT THE MIAMI FOUNDATION, REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF THE ARTIST. PHOTO: DANIEL AZOULAY PHOTOGRAPHY.

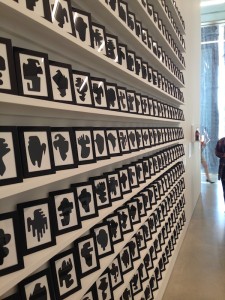

Allan McCollum, The Shapes Project, Collection of One Hundred and forty-four Monoprints, 2005-2006, 144 framed monoprints, in “Commodity Cultures.” COURTESY DARLENE AND JORGE M. PÉREZ. PHOTO: ROBIN CEMBALEST.

When an artist puts boats on the ceiling, it’s a gesture calling for a change in perspective, so that’s just one of the messages the Pérez Art Museum Miami is sending in its resplendent new lobby, where Hew Locke’s festive, motley fleet dangles before the huge glass walls that look out on Biscayne Bay.

The work, titled For Those in Peril on the Sea, has been shown elsewhere, but it takes on a special relevance in this city, where so many of “those” people came by sea. Yet another message the museum makes clear right away is that terms like “us” and “those,” “insider” and “outsider,” don’t matter in this venue, where the outside–the light, the sun, the green from the surrounding park—streams inside Herzog and de Meuron’s low-lying structure, which finally gives Miami the art museum it deserves and the rest of us some ideas about the art museum of the future.

The museum stakes its claim to the future with a quiet authority, and without any suggestion that it’s trying to play catch-up with the big guys. A “polyvocality of storytelling,” to use one of director Thom Collins’s catch phrases, is the ongoing theme, especially in the main exhibition showcasing the collection (and some strategic loans), “Americana.” It’s a familiar term cleverly repurposed and repackaged to sidestep definitions, presenting identity as something that matters, but doesn’t limit.

Pérez Art Museum Miami. PHOTO: IWAN BAAN.

Artists from North American, Caribbean, and South American backgrounds converge here, grouping off in sections with themes like craft, landscape, consumerism, violence, identity, and geometry and conversing so eloquently among themselves that the curatorial team, led by Tobias Ostrander, was able to avoid the kind of long-winded labels that tell viewers what they’re supposed to take away from all this. (The labels, by the way, are all in both English and Spanish.)

Polly Apfelbaum, Mojo Jojo (detail), 2001, velvet and dye, in “Formalizing Craft.” COLLECTION PÉREZ ART MUSEUM MIAMI, MUSEUM PURCHASE WITH FUND PROVIDED BY THE PAMM COLLECTORS COUNCIL AND THE HELENA RUBINSTEIN FOUNDATION. PHOTO: DANIEL AZOULAY PHOTOGRAPHY.

Each installation draws out the artists’ relationships to society, art history, and each other. Duchamp and Warhol and other heavy hitters are present, but they hardly take center stage, and anyway the message of this show that influence moves in many directions, geographically and otherwise. So in “Progressive Forms,” Judd, LeWitt, Albers, and, less expected, Joseph Cornell (who loved his maps) are among those who take their place alongside Gego, Julio Alpuy, Alexander Apóstol, and Lygia Clark; while “Formalizing Craft” unites Betty Woodman’s Aztec Vase 7 with ceramic work by Hannah Wilke and Gabriel Orozco, fabric pieces by Al Loving, Sanford Biggers, and Polly Apfelbaum, and Adrian Esparza’s woven and unwoven serape–to name some. “Desiring Landscape” features unlikely partners Fernando Botero, Xaviera Simmons, Mark Dion, and Lisa Yuskavage, but it all makes sense.

Xaviera Simmons, Untitled (Pink), 2009, color photograph, in “Desiring Landscape.” COLLECTION PÉREZ ART MUSEUM MIAMI, MUSEUM PURCHASE WITH FUNDS PROVIDED BY JORGE AND DARLENE PÉREZ AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION PHILANTHROPIC FUND. ©XAVIERA SIMMONS/COURTESY DAVID CASTILLO GALLERY, MIAMI.

There is plenty more here, including the mesmerizing “Selections from the Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry;” an exhibition devoted to Cuban Modernist Amelia Peláez; a photo gallery that forces you to look at an iPad to figure out what’s what (whither Google Glass?); a new Yael Bartana video; project galleries devoted to Bouchra Khalili and Monika Sosnowska, and a vast, vast show devoted to Ai Weiwei, whose playful Zodiac animal heads adorn the outdoor terrace.

Oscar Muñoz, Cortinas de baño, 1994, acrylic on plastic, in “Corporal Violence.” COLLECTION PÉREZ ART MUSEUM MIAMI, GIFT OF GEORGE M. SAFIRSTEIN M. D. AND POLA REYDBURD. PHOTO: DANIEL AZOULAY PHOTOGRAPHY.

Sure, it’s a calculated internationalism, but this museum never loses sight of the fact that the global is now the local—or, more importantly, of the beauty and mystery that lure people to art museums in the first place. It’s a place to look, to think, and to be.

Ai Weiwei, Stacked, 2002, 680 stainless steel units, in “Ai Weiwei: According to What?” PHOTO: DANIEL AZOULAY PHOTOGRAPHY.

Copyright 2013, ARTnews LLC, 48 West 38th Street, New York, N.Y. 10018. All rights reserved.

By Robin Cembalest

Source: http://www.artnews.com