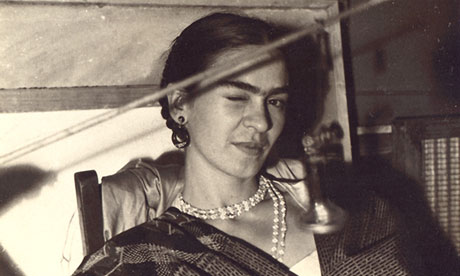

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera at the Bowes Museum

An odd couple take over the former home of another odd couple. No wonder Frida Kahlo’s winking. The Guardian Northerner‘s arts ace Alan Sykes explains

Frida Kahlo. Some character. If you haven't already read Barbara Kingsolver's 'The Lacuna', do. It's a warmly imaginative account of the curious pair. Photograph: Lucienne Bloch

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera made a pretty odd couple – Rivera the much older, much travelled, much married friend of Modigliani and Picasso, Kahlo the Hungarian-Jewish-Spanish-Mexican surrealist painter from the Casa Azul. The Bowes Museum’s founders John and Josephine Bowes weren’t exactly conventional either – he the race horse-owning illegitimate heir to 43,200 acres and a large chunk of the Durham coalfield, she a grande horizontale actress turned obsessive collector.

According to the Bowes’ head of exhibitions, Vivien Vallack, the museum’s visitors are interested in photography exhibitions as well as the many other two and three dimensional delights of their treasure house in the Dales. So when the Mexican Embassy offered her the chance to be the only place in Britain to host an exhibition of photographs documenting the extraordinary lives of Kahlo and Rivera, she jumped at it.

The long and bloody Mexican revolution was fortunate in having Rivera as its unofficial “artist in residence” – with Jacques-Louis David and the French revolution arguably the only other one with a great artist on hand to record it. After Rivera’s early cubist period, he tended towards a socialist realist figuration, but his work can also be said to hark back to the fresco painting tradition of renaissance Italy – with workers and their struggles as the subject of his murals, rather than princes and their battles. Although a communist, he got on surprisingly well with American millionaires – he created “Detroit Industry”, a huge mural for Henry Ford, another for the New York Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, as well as a commission from the Rockefellers. In an act of astonishing vandalism, the Rockefeller Center in New York, having commissioned him to create “Man at the Crossroads” a giant mural for the ground floor wall of the centre, took exception to the fact that Rivera had inserted a portrait of Lenin, leading the managers to destroy the entire work. Rivera got his revenge, as he used his fee from the Rockefellers to paint another portrait of Lenin (this time with Trotsky) as part of a mural in the Independent Labour Institute in Mexico City. One of the photographs here shows Kahlo typing a letter of protest which Rivera is dictating about the removal of the mural.

Little and large, but equally strong-minded. Kahlo's reputation has lately overhauled Rivera's. Photograph: Bowes Museum

Frida Kahlo said:

I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One involved a bus, the other is Diego.

Diego was more than double her age when they met, and the marriage was stormy – or rather marriages, as they divorced and then got together again. It was while Rivera was working for Ford in Detroit that Kahlo painted Miscarriage in Detroit, one of the first of her self-portraits. Rivera said of it:

Frida began work on a series of masterpieces which had no precedent in the history of art – paintings which exalted the feminine quality of truth, reality, cruelty and suffering. Never before had a woman put such agonized poetry on canvas as Frida did at this time in Detroit.

One of the photographs here shows her working in her studio under her double self-portrait, The Two Fridas, one of which has her heart cut open, while the other, heart intact, holds a miniature of Rivera, which was painted while the couple were divorced.

Another of her admirers was the French surrealist Andre Breton, who visited Mexico in 1938, and described it as a “surrealist country par excellence“.

When Trotsky, chased out of Norway by Stalin’s pressure, arrived in Mexico in 1938, he stayed with the couple, and Frida’s affair with him was one of the factors that led to her brief divorce. Here is a YouTube clip of the three of them together, with twangy Mexican guitar accompaniment.

Whether Rivera was actively complicit in Trotsky’s murder does not seem to be proven, but the fact that the assassins used his truck in their attack is suspicious, to say the least.

The photographs in this exhibition form a timeline that documents the two artists’ lives. Photographs from both weddings are here, and the first known photograph of the couple, at a May Day rally in 1929, while a poignant last picture of them together was taken in 1952, with both clearly unwell. The last picture of Frida shows that she never lost her revolutionary zeal – despite having had her gangrenous leg amputated, she is pictured, only 11 days before her death in 1954, attending a demonstration against the CIA’s overthrow of Guatemala’s democratically elected president, Jacobo Arbenz.

Supper at San Angel; another of the pictures in the Bowes exhibition. Photograph: Louis Riley

This exhibition has been organised by the Mexican Foreign Office and the National Institute of Fine Art in Mexico City. It is a part of the Vamos festival of Latin and Lusiphone events and exhibitions happening across the North East in June and July.

By Alan Sykes

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk