Malevich review – an intensely moving retrospective

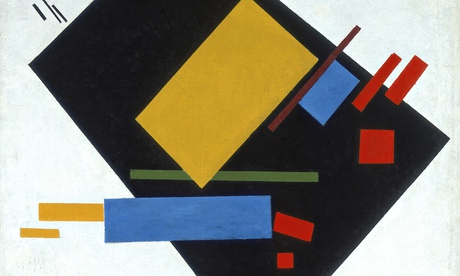

‘Total euphoria’: Malevich's Suprematist Painting (with Black Trapezium and Red Square), 1915. Photograph: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

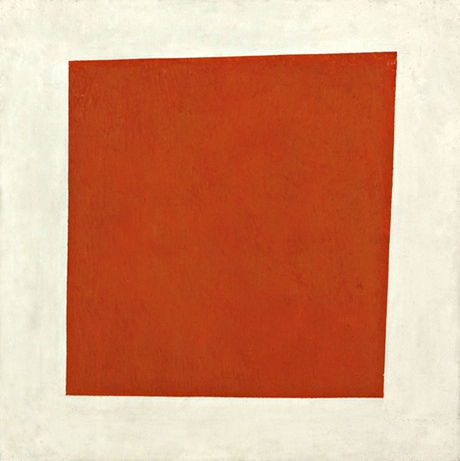

Kazimir Malevich painted his revolutionary Red Square one hundred years ago. It still looks staggeringly new at Tate Modern. Even after a century of abstract art nothing seems quite so radical as this dazzlingly simple form – more parallelogram than square – leaping into scarlet life out of pure white space, tilting eagerly forwards. The painting remains for ever young.

To see it in this intensely moving retrospective – the first in Britain since Malevich’s death in 1935, isolated, impoverished, purged by Stalin – is to realise just how romantic the painter’s dream of art could be. Suprematism, the movement he pioneered, believed in the radical reduction of painting to nothing but shape and colour. Paintings would not be pictures, they would depict nothing, state nothing, resist all aesthetic conventions. They would spring free as the revolution itself.

There is a heroic daring in the self-sufficiency of Malevich’s art, which relies on nothing but its own fierce beauty at a time when his contemporaries were still turning out icons and onion domes.

Malevich was the eldest of 14 children born to Polish parents in Kiev in 1879, when Tsar Nicholas II ruled Russia. Eighty per cent of the population were classed as serfs. Red Square may be decisively abstract but it is subtitled Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions, and there is no mistaking the life force conveyed in that advancing form, nor the free spirit, no matter that the woman isn’t shown.

There is no plane in Airplane Flying either, and no boy in Painterly Realism of a Boy With a Knapsack, both made in 1915. Yet these arrays of brilliant rectilinear shapes give the most exhilarating sensation of movement – of soaring upwards, of marching onwards – without the slightest hint of figuration. Geometry and colour were all Malevich needed to speak of freedom.

Red Square (Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions), 1915. Photograph: State Russian Museum, St Petersburg

1915 is year zero for suprematism, the momentous year in which Malevich unleashed his brave new non-objective art upon the first stunned witnesses to the legendary 0.10 exhibition in Petrograd. It is not the least thrill of this show that the curators have somehow managed to assemble nine of those works (the rest are lost or suppressed, like so many of his paintings) exactly as they were seen on that day.

They make you wait for this – as they should, so that the anticipation builds like steam in a kettle – with several rooms of early avant-garde clutter. Malevich tried everything out, from impressionism to cubism to futurist machines. In all these rehearsals there are performances of his own – the fantastic tubular peasant with his elegant toes and beard like a gleaming steel trowel; the snowstorm where the villagers are red and blue cylinders in the whiteout, hint of shapes to come – but the main interest is in the Cyrillic script or the cubist samovar.

And in seeing just how fast Malevich left all this behind him when he flew: when you reach the 1915 gallery there is a rush of energy, a feeling of release which must surely echo Malevich’s own sense of breaking free. The paintings are such radical reductions – pure colours, plain shapes, white ground – yet all the elements conspire to generate complex motion. The red parallelogram presses forward, the black cross bends and gyrates in its white square, a disc spills from a triangle like a vivacious bubble.

The paintings are displayed exactly as they were, eccentrically, rising up to the great Black Square hung high and across a corner, connecting two walls, just as icons were mounted in homes all across Russia. Except that this icon has no face, only the strength of its voluminous blackness which is both bewildering and rich. It ought to be funereal, or blank, or as null as its name suggests but it too sparks with vitality.

You are in at the birth of a new thing breathing, as it seems; there is an air of total euphoria.

The surprise of these paintings is not just to do with their unfamiliarity – hidden, forgotten in provincial museums, banned for much of the 20th century – it is in their essential abruptness. Each painting unleashes itself like a firework, each has agency, action, charge. If some paintings are nouns, these are all verbs.

Everything uplifts, and everything soars. It is almost a limitation, from our end of the space age, that so many of Malevich’s suprematist paintings resemble jet planes, rockets, capsules in outer space, since he could have no idea of such inventions and certainly aimed way beyond figuration. But he did speak of himself and his colleagues as aviators, and even when suprematist painting was beginning to fade – he was done with it by the 1920s, staging its passing in a series of ethereal monochromes in which squares and crosses dissolve in pale mist – there is a sense of trying to loose the bonds of Earth.

The 0.10 exhibition in Petrograd, 1915, at which Malevich unleashed his brave new non-objective art. Photograph: Collection of Charlotte Douglas, New York

Come the revolution, suprematism becomes a design for living. Malevich produces posters, stage costumes, designs for teapots and cups (or rather half-cups, bisected so that one suddenly sees into a quartered sphere as never before). He becomes a teacher, travels to Berlin and Vitebsk. His teaching materials are so dynamically beautiful they have a room here all to themselves.

And so too his prolific works on paper – cartoons, portraits, visions, abstracts: a life’s work in miniature on ever more meagre scraps. If you didn’t know he would be arrested for spying, punished for his radicalism, disgraced and eventually impoverished, you might guess some of it from this selection. A late watercolour reprise of the red square is still trying to take off, one corner delicately lifting free from the white surround. No less affecting, it is only a couple of inches across.

Malevich wrote much and said more about suprematism, his utterances veering between vigorous idealism, apocalyptic nihilism and a hazy eloquence so open to interpretation it has been construed without consensus many ways. Mercifully this show does not strive for definition in its wall texts.

But what one sees in this show are paintings that do not picture the world, yet speak of (and extend) its infinite variety with a visual language all of their own. It is an art of utter originality.

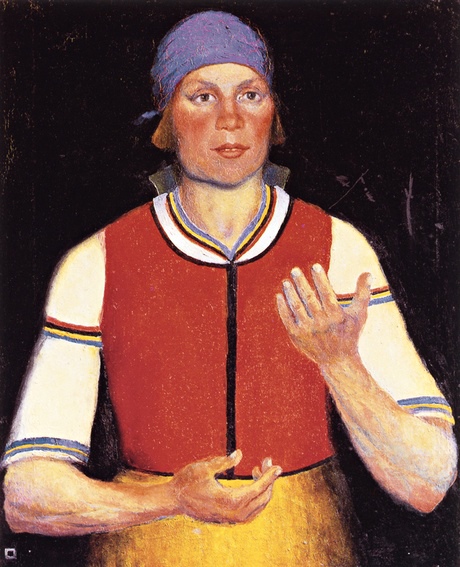

Woman Worker, 1933, by which time Malevich had been ‘forced to go backwards, to paint (almost) in the approved socialist realist manner’. Photograph: State Russian Museum, St Petersburg

The final room is shattering. The story reaches tragedy as no other exhibition in the history of Tate Modern; what you see is the aviator shot down. Malevich is forced back to Earth, forced to go backwards, to paint (almost) in the approved socialist realist manner. The peasant woman appears in headscarf and apron. The worker stands proud with his Stalin moustache.

There are poignant souvenirs of Malevich’s radical past if you look – the future, as it might have been, in the blacksmith’s vibrant uniform, in the wild clothes he gives the Russian workers, in the triangles jigsawed together in his 1933 self-portrait. But this self-portrait is otherwise so like the one that opens this show, painted more than 20 years earlier, as to measure the loss. All that remains of this brief, brave adventure is the secret motif in place of a signature – a tiny black square.

In 1935, the year Malevich died of cancer at the age of 56, two of his canvases reached America furled inside an umbrella. A few more were smuggled into the Netherlands. But most of his work was censored, destroyed or obscured by the silt of Stalinist dross, lost to the world – Russians included – for decades. But back they come as if raised from the dead – the red square, the black square and the white, these inexhaustible beacons of modern painting, and nothing now can put out their light.

By Laura Cumming

Source: http://www.theguardian.com