Doyen of American critics turns his back on the ‘nasty, stupid’ world of modern art

Dave Hickey condemns world he says has become calcified by too much money, celebrity and self-reverence.

One of America’s foremost art critics has launched a fierce attack on the contemporary art world, saying anyone who has “read a Batman comic” would qualify for a career in the industry.

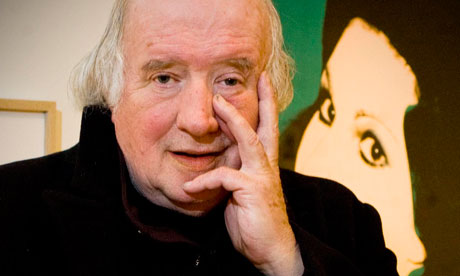

Dave Hickey, a curator, professor and author known for a passionate defence of beauty in his collection of essays The Invisible Dragon and his wide-ranging cultural criticism, is walking away from a world he says is calcified, self-reverential and a hostage to rich collectors who have no respect for what they are doing.

“They’re in the hedge fund business, so they drop their windfall profits into art. It’s just not serious,” he told the Observer. “Art editors and critics – people like me – have become a courtier class. All we do is wander around the palace and advise very rich people. It’s not worth my time.”

Hickey says the art world has acquired the mentality of a tourist. “If I go to London, everyone wants to talk about Damien Hirst. I’m just not interested in him. Never have been. But I’m interested in Gary Hume and written about him quite a few times.”

If it’s a matter of buying long and selling short, then the artists he would sell now include Jenny Holzer, Richard Prince and Maurizio Cattelan. “It’s time to start shorting some of this shit,” he added.

Hickey’s outburst comes as a number of contemporary art curators at world famous museums and galleries have complained that works by artists such as Tracey Emin, Antony Gormley and Marc Quinn are the result of “too much fame, too much success and too little critical sifting” and are “greatly overrated”.

Speaking on condition of anonymity to Will Gompertz, the BBC’s arts editor, one curator described Emin’s work as “empty”, adding that because of the huge sums of money involved “one always has to defend it”.

Gompertz, who recently wrote What Are You Looking At? 150 Years of Modern Art, sympathised with Hickey’s frustration.

“Money and celebrity has cast a shadow over the art world which is prohibiting ideas and debate from coming to the fore,” he said yesterday, adding that the current system of collectors, galleries, museums and art dealers colluding to maintain the value and status of artists quashed open debate on art.

“I hope this is the start of something that breaks the system. At the moment it feels like the Paris salon of the 19th century, where bureaucrats and conservatives combined to stifle the field of work. It was the Impressionists who forced a new system, led by the artists themselves. It created modern art and a whole new way of looking at things.

“Lord knows we need that now more than anything. We need artists to work outside the establishment and start looking at the world in a different way – to start challenging preconceptions instead of reinforcing them.”

Gompertz said Hickey was not a man who ever regretted a decision but that he did not agree with the American that the whole contemporary art world was moribund. “There are important artists like Ai Weiwei and Peter Doig, who produces beautiful and haunting paintings in similar ways to Edward Hopper,” he said.

As a former dealer, Hickey is not above considering art in terms of relative valuation. But his objections stem from his belief that the art world has become too large, too unfriendly and lacks discretion. “Is that elitist? Yes. Winners win, losers lose. Shoot the wounded, save yourself. Those are the rules,” Hickey said.

His comments come ahead of the autumn art auctions. With Europe in recession and a slowdown in the Chinese and Latin American economies, vendors are hoping American collectors, buoyed by a 2% growth in the US economy, andnew collectors, such as those coming to the market from oil-rich Azerbaijan, will boost sales.

At 71, Hickey has long been regarded as the enfant terrible of art criticism, respected for his intellectual range as well as his lucidity and style. He once said: “The art world is divided into those people who look at Raphael as if it’s graffiti, and those who look at graffiti as if it’s Raphael, and I prefer the latter.”

Hickey, who also rates British artist Bridget Riley, says he did not realise when he came to the art world in the 1960s that making art was a “bourgeois” activity.

“I used to sell hippy art to collectors and these artists now live like the collectors I used to sell to. They have a house, a place in the country and a BMW.”

Hickey says he came into art because of sex, drugs and artists like Robert Smithson, Richard Serra and Roy Lichtenstein who were “ferocious” about their work. “I don’t think you get that anymore. When I asked students at Yale what they planned to do, they all say move to Brooklyn – not make the greatest art ever.”

He also believes art consultants have reduced the need for collectors to form opinions. “It used to be that if you stood in front of a painting you didn’t understand, you’d have some obligation to guess. Now you don’t,” he says. “If you stood in front of a Bridget Riley you have to look at it and it would start to do interesting things. Now you wouldn’t look at it. You ask a consultant.”

Hickey says his change of heart came when he was asked to sign a 10-page contract before he could sit on a panel discussion at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Laura Cumming, the Observer’s art critic, said it would be a real loss if Hickey stopped writing commentary. “The palace Hickey’s describing, with its lackeys and viziers, its dealers and advisers, is more of an American phenomenon. It’s true that we too have wilfully bad art made for hedge fund managers, but the British art scene is not yet so thick with subservient museum directors and preening philanthropists that nothing is freely done and we can’t see the best contemporary art in our public museums because it doesn’t suit the dealers.And that will be true, I hope, until we run out of integrity and public money.”

Hickey’s retirement may only be partial. He plans to complete a book, Pagan America — “a long commentary of the pagan roots of America and snarky diatribe on Christianity” — and a second book of essays titled “Pirates and Framers.”

It is the job of a cultural commentator to make waves but Hickey is adamant he wants out of the business. “What can I tell you? It’s nasty and it’s stupid. I’m an intellectual and I don’t care if I’m not invited to the party. I quit.”

By Edward Helmore and Paul Gallagher

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk