Fruits of the Vineyard

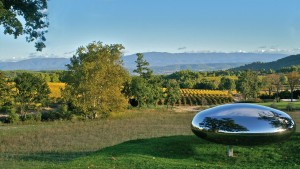

Tom Shannon’s 2009 sculpture Drop reflects Château La Coste’s sprawling landscape. LARRY NEUFELD/©2012 CHÂTEAU LA COSTE AND TOM SHANNON

For decades, the ancient vineyard of Château La Coste, located on a rolling 600-acre plain near Aix-en-Provence, was a sleeping beauty waiting to be brought to life. Once the center of a major wine-producing region cultivated as early as the Roman times, and a rest stop for pilgrims on the way to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, the property had seen far better days when Irish real-estate developer and art collector Paddy McKillen purchased it in 2002. Convinced that wine-making is “a noble task,” McKillen resolved to restructure the vineyards and to introduce the latest biodynamic standards for their cultivation. At the same time, he realized that La Coste would be a wonderful setting for art.

With that in mind, he invited leading architects and artists to come to La Coste and propose projects that could be realized on its historic terrain. Today, five Pritzker Prize winners and a score of sculptors have left their marks there. With Aix (2008), for example, Richard Serra inserted vast sheets of steel into a hillside at varying angles, like skewed steps. Sean Scully’s signature geometries are realized in the myriad cuts and colors of stone that make up his Wall of Light Cubed from 2007. And Franz West accented the vineyard’s promenade with his bright yellow Faux-Pas (2006), a kind of phallic totem that straddles the line between sculpture and furniture.

The first new structure on the property was the two-part, gravity-flow chai (winery), designed by Jean Nouvel and completed in 2008. Although a nearby 17th-century Palladian-style château with a miniature, baroque garden had long set the architectural tone for the landscape, Nouvel’s gleaming, elegant structure of corrugated aluminum seemed to transport the domain into a new millennium. The winery was soon joined by Frank Gehry’s Music Pavilion, while Tadao Ando’s minimalist “information center” slowly took shape.

In one of the center’s three reflecting pools, a monumental spider by Louise Bourgeois perches above the surface; the second pool holds an Alexander Calder stabile, and the third showcases Hiroshi Sugimoto’s conical Infinity (2010), which rises from the water and tapers to a point no more than one millimeter in diameter. Shimmering in the light beneath the intense blue skies of Provence, Ando’s building and Sugimoto’s sculpture seem almost to dematerialize, while the pools surrounding Ando’s structure reflect the verdant surrounding hillsides. The entire complex encourages a zen-like quiet and introspection.

Ando’s chapel, perched on La Coste’s highest ridge, is a renovated structure that was once a stop for those 16th-century pilgrimages. Completely overgrown when McKillen acquired the property, it was believed by locals to be a former shepherd’s hut, or a gardening shed. Ando stripped the structure of vegetation, took it apart stone by stone, and meticulously reconstructed it, finally encasing it in a glass cube. Its new roof sits slightly higher than the top of the walls, so that by day a narrow band of sunlight filters in.

In the chapel, as with British artist Andy Goldsworthy’s nearby Oak Room (2009), silence feels almost tangible. For Goldsworthy’s permanent installation, he literally wove together the trunks of oak trees cleared from a nearby forest to create a kind of cave within a hillside—a monumental, cathedral-like space that is one of the many surprises awaiting visitors to La Coste. A tour of the property presently takes about 90 minutes, but with new works being added constantly, that duration is certain to expand.

One of the latest projects there involves the erection of a pair of prefabricated houses—among the first of their kind—that Jean Prouvé designed for World War II refugees in 1945. Of the 450 structures originally built, these are perhaps the sole survivors. Restored under the supervision of the architect’s son Nicolas, they now house art libraries fitted with original Prouvé furniture. Linking them is a rare, 17th-century Viet-namese teahouse pavilion, where visitors can sip tea and browse through the objects housed in the adjacent libraries. Meanwhile, work has begun on a bell tower by Henri Matisse’s grandson Paul, a light tunnel by James Turrell, a pair of bridges by Norman Foster, and a Renzo Piano–designed building for aging grand cru wines. Most of this structure is to be underground, but an upper level will house a photography center.

The bulk of a five-star hotel, conceived for the site by Marseille’s Tangram Architects and scheduled for completion late next year, is also to be located underground, embedded in the Provençal landscape. Other exhibition spaces, research facilities, and a cooking school are on the drawing board, as is a concert hall designed by the world’s oldest living architect, the 105-year-old Oscar Niemeyer. A series of organic gardens is being developed by French landscape designer Louis Benech.

The power behind this grandiose fusion of art, architecture, viniculture, history, and landscape is a man who does not give interviews, rarely appears in public, has almost never been photographed, and is more often cited by journalists on the financial page—not always approvingly—than in the culture section. Employing classic British understatement, Richard Rogers, codesigner of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, has remarked, “Paddy is our quietest client.”

But the true voice, and perhaps even the soul, of Château La Coste is that of McKillen’s sister Mara, who manages the domain and recounts her experiences there in a lilting Belfast accent. It was Mara who visited Provence in 1990 “to follow a dream,” discovered the legendary “Monday Market” of Forcalquier, and began writing a book on Provence. That enthusiasm is now focused on restoring the vineyards to their former glory. “It’s all about having respect for the creative process,” she says, “whether in winemaking or in architecture.” When she describes walking through the vineyards and collecting shards of Roman pottery that have been washed up by the rain, her intense love of the land is as evident as her brother’s passion for art and architecture.

With minimal publicity, La Coste is now attracting as many as 200 visitors a day, and that number is likely to skyrocket next year, when Marseille will enjoy a year-long stint as the designated European Capital of Culture. The Mediterranean port city intends to spend the year focusing on the performing arts, while the visual arts will be represented by exhibitions in nearby Aix and throughout the surrounding region. Many who make that cultural pilgrimage may consider Château La Coste a worthwhile stop.

By David Galloway

Source: www.artnews.com